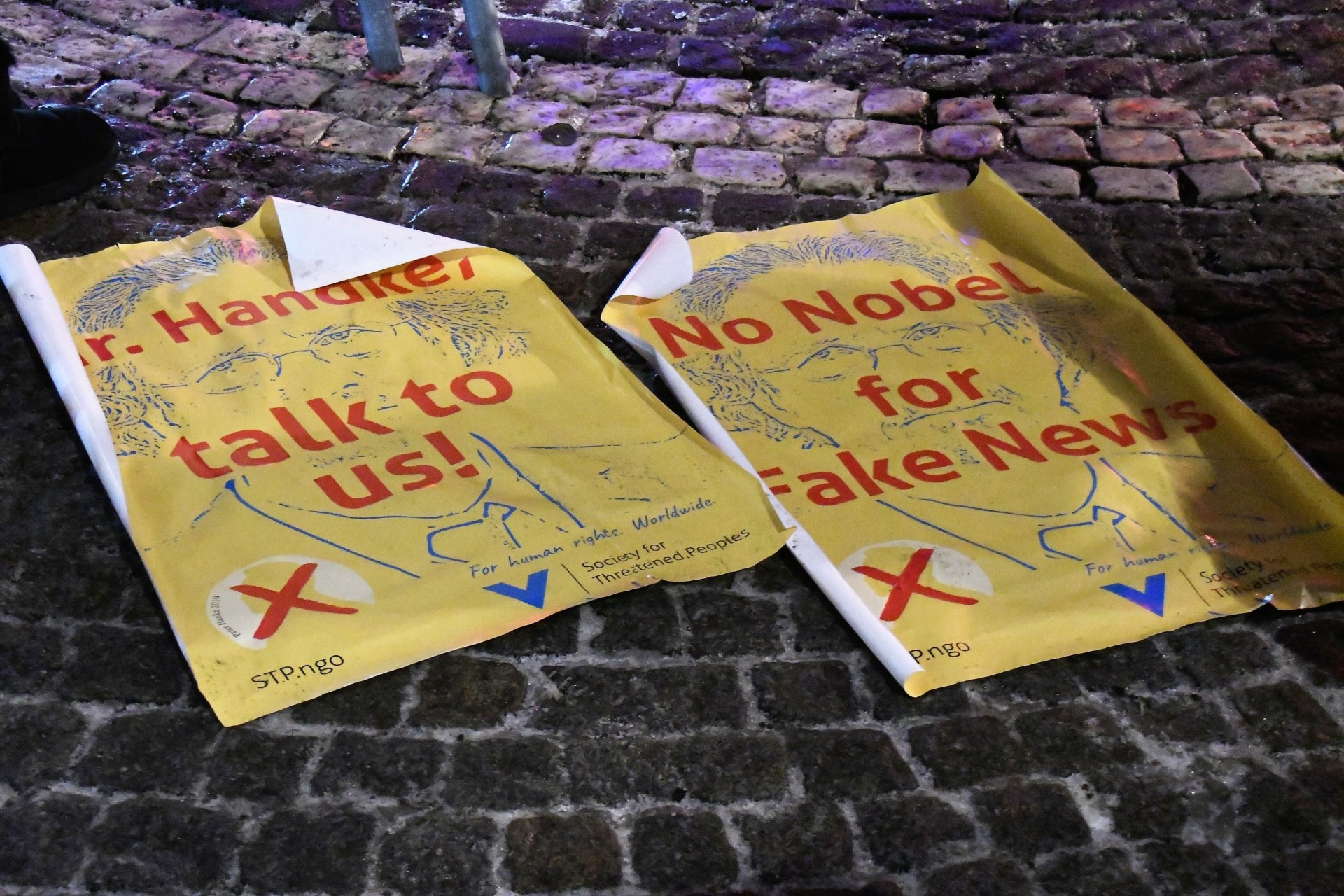

Ahhh, thank you! I just saw this!Excellent and perceptive article on the genocide denialism in Handke by a professor of Balkan history:

A Literary Consecration of Genocide Denial

The Swedish Academy’s embrace of Handke comes at a time when far-right movements worldwide have also seized elements of 1990s Serbian nationalism as fuel for violent fantasies from Utøya, Norway, to Christchurch, New Zealand.newlinesmag.com

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Peter Handke

- Thread starter Stewart

- Start date

MichaelHW

Active member

When I was younger, I remember finding Hancke in my mother's bookshelf. At the time, I thought he wrote in a very pretentious and intellectual way. I think even my mother thought so. What I would think now, I don't know? The nobel prize has turned into a celebration of European intellectual snobbery. Some of the writers are wonderful, but some of the others you can see are geniuses, but there is something about them that pushes you in the direction of Ken Follett. Perhaps some books are better to own than to read?

Cool take! Coincidentally, I read my first Handke (“The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick”) like…a week before he won the Nobel, maybe? At the time, I didn’t think much of that book. After he won, I decided to give his work another chance, mostly because I’ve discovered several of my favourite writers via the Nobel and similar awards…my idea being that, if the SA saw fit to award him, I’d give his work another chance.

Let me explain. I’ve had a similar ‘issue’ with other laureates at first glance. I remember the year Modiano won. The only book of his available where I live was the “Occupation” trilogy, the first novella of which is an irreverent, ‘enfant terrible’ thing he wrote at like 22 or something. I remember reading it, thought it was pretentious, silly, affected, very…well, elitist and rude at the same time. I didn’t finish it, or read the other two novellas in the collection.

A few years later, I stumbled across some $5 editions of his stuff. I thought…what the heck, $5, only 100-odd pages, Nobel laureate, why not? Basically…in those three, four books…I perceived a certain elusive sensibility in Modiano, one which developed more from further readings. Today, he’s one of my favourite authors.

I’ve had a very similar experience with Handke. “Goalie” felt…meh. After that (remembering the Modiano challenge) I tried “Moravian Nights,” which felt…locked to me, like, beautifully crafted in a way which felt completely beyond me. It made me feel a bit clueless, lol, but in a good way, like being blindsided by beauty.

Next, I did a couple more of his short novels, liked them in that same vague way, but still felt ‘out to sea.’ It was only when I found his journal, “The Weight of The World,” that I became intrigued. It’s written in a poetic, aphoristic way I really liked. That book really hit home for me…and seen in that light, I found his other work a lot more illuminating.

I get what you mean with the whole Follett thing. With most writers…yeah, I’ll put them down after 50, 100 pages if they just aren’t ‘clicking’ for me. It’s different with the Nobel. They’ve delivered (for me, anyway) many times before, have introduced me to many a fine writer who I may never have found otherwise.

This isn’t to say I’ve ‘gotten’ every choice the SA has ever made. In fact, many of them still ‘elude’ me in the sense that they’re outside my current frame of reference. I will say, though, that I’m glad I was patient with Handke. Reading him now feels very…if you’ll forgive the cliche…’meta.’ I feel like he’s less about typical concepts like plot, linearity, etc (or at least leaves them open to interpretation) and more about redefining the very ways in which we see the world.

Then again…that’s just me, lol. I could be totally off-base, have little formal education when it comes to this stuff, just enjoy it!!! Meanwhile…you make me want to check out Follett again, lol. ?

Let me explain. I’ve had a similar ‘issue’ with other laureates at first glance. I remember the year Modiano won. The only book of his available where I live was the “Occupation” trilogy, the first novella of which is an irreverent, ‘enfant terrible’ thing he wrote at like 22 or something. I remember reading it, thought it was pretentious, silly, affected, very…well, elitist and rude at the same time. I didn’t finish it, or read the other two novellas in the collection.

A few years later, I stumbled across some $5 editions of his stuff. I thought…what the heck, $5, only 100-odd pages, Nobel laureate, why not? Basically…in those three, four books…I perceived a certain elusive sensibility in Modiano, one which developed more from further readings. Today, he’s one of my favourite authors.

I’ve had a very similar experience with Handke. “Goalie” felt…meh. After that (remembering the Modiano challenge) I tried “Moravian Nights,” which felt…locked to me, like, beautifully crafted in a way which felt completely beyond me. It made me feel a bit clueless, lol, but in a good way, like being blindsided by beauty.

Next, I did a couple more of his short novels, liked them in that same vague way, but still felt ‘out to sea.’ It was only when I found his journal, “The Weight of The World,” that I became intrigued. It’s written in a poetic, aphoristic way I really liked. That book really hit home for me…and seen in that light, I found his other work a lot more illuminating.

I get what you mean with the whole Follett thing. With most writers…yeah, I’ll put them down after 50, 100 pages if they just aren’t ‘clicking’ for me. It’s different with the Nobel. They’ve delivered (for me, anyway) many times before, have introduced me to many a fine writer who I may never have found otherwise.

This isn’t to say I’ve ‘gotten’ every choice the SA has ever made. In fact, many of them still ‘elude’ me in the sense that they’re outside my current frame of reference. I will say, though, that I’m glad I was patient with Handke. Reading him now feels very…if you’ll forgive the cliche…’meta.’ I feel like he’s less about typical concepts like plot, linearity, etc (or at least leaves them open to interpretation) and more about redefining the very ways in which we see the world.

Then again…that’s just me, lol. I could be totally off-base, have little formal education when it comes to this stuff, just enjoy it!!! Meanwhile…you make me want to check out Follett again, lol. ?

MichaelHW

Active member

Ken Follett is actually a wonderful writer in his own genre. If you look at his sentences, they are simple, clear and very unpretentious. He wrote a delightful novel once about a sea plane traveling to Europe just before WWII. For some reason, that book has always been one of my favorites. As he grew more experienced and respected, however, he got it into his head that he had to write long epic chronicles spanning decades, if not hundreds of years. I think he became a meglomaniac ? Perhaps he wanted to be taken more seriously, I don't know? Then he lost me as a reader. But his old thrillers are wonderful.Cool take! Coincidentally, I read my first Handke (“The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick”) like…a week before he won the Nobel, maybe? At the time, I didn’t think much of that book. After he won, I decided to give his work another chance, mostly because I’ve discovered several of my favourite writers via the Nobel and similar awards…my idea being that, if the SA saw fit to award him, I’d give his work another chance.

Let me explain. I’ve had a similar ‘issue’ with other laureates at first glance. I remember the year Modiano won. The only book of his available where I live was the “Occupation” trilogy, the first novella of which is an irreverent, ‘enfant terrible’ thing he wrote at like 22 or something. I remember reading it, thought it was pretentious, silly, affected, very…well, elitist and rude at the same time. I didn’t finish it, or read the other two novellas in the collection.

A few years later, I stumbled across some $5 editions of his stuff. I thought…what the heck, $5, only 100-odd pages, Nobel laureate, why not? Basically…in those three, four books…I perceived a certain elusive sensibility in Modiano, one which developed more from further readings. Today, he’s one of my favourite authors.

I’ve had a very similar experience with Handke. “Goalie” felt…meh. After that (remembering the Modiano challenge) I tried “Moravian Nights,” which felt…locked to me, like, beautifully crafted in a way which felt completely beyond me. It made me feel a bit clueless, lol, but in a good way, like being blindsided by beauty.

Next, I did a couple more of his short novels, liked them in that same vague way, but still felt ‘out to sea.’ It was only when I found his journal, “The Weight of The World,” that I became intrigued. It’s written in a poetic, aphoristic way I really liked. That book really hit home for me…and seen in that light, I found his other work a lot more illuminating.

I get what you mean with the whole Follett thing. With most writers…yeah, I’ll put them down after 50, 100 pages if they just aren’t ‘clicking’ for me. It’s different with the Nobel. They’ve delivered (for me, anyway) many times before, have introduced me to many a fine writer who I may never have found otherwise.

This isn’t to say I’ve ‘gotten’ every choice the SA has ever made. In fact, many of them still ‘elude’ me in the sense that they’re outside my current frame of reference. I will say, though, that I’m glad I was patient with Handke. Reading him now feels very…if you’ll forgive the cliche…’meta.’ I feel like he’s less about typical concepts like plot, linearity, etc (or at least leaves them open to interpretation) and more about redefining the very ways in which we see the world.

Then again…that’s just me, lol. I could be totally off-base, have little formal education when it comes to this stuff, just enjoy it!!! Meanwhile…you make me want to check out Follett again, lol. ?

Last edited:

I believe it! That novel you’ve described sounds cool…is KF anything like Graham Greene? I guess you have me picturing this avuncular-type figure whose stuff seems to ‘entertain’ initially before coalescing into some really profound thing. Meanwhile, here I am still working on good ol’ PH, lol.Ken Follett is actually a wonderful writer in his own genre. If you look at his sentences, they are simple, clear and very unpretentious. He wrote a delightful novel once about a sea plane traveling to Europe just before WWII. For some reason, that book has always been one of my favorites. As he grew more experienced and respected, however, he got it into his head that he had to write long epic chronicles spanning decades, if not hundreds of years. I think he became a meglomaniac ? Perhaps he wanted to be taken more seriously, I don't know? Then he lost me as a reader. But his old thrillers are wonderful.

I can see how this guy gets pegged as a ‘living classic.’ His stuff messes with my head (in a good way). The effect is psychedelic for me. I get why he wrote a whole novel about some guy who really, um, liked mushrooms.

Has anyone else here either pre-ordered “The Fruit Thief” or read it in another language? I think someone here said it was a factor in the SA awarding him. I can’t wait to read it, but have to wait for the English edition. ?

The reason why I bring it up is because I’m wondering if anyone else noticed how PH mentions the ‘fruit thief’ concept in a couple of other books. He refers to it in “Crossing the Sierra de Gredos” as a centrally defining image in the banker’s life. He mentions it somewhere else too…I want to say “Moravian Nights,” but I’m not positive, will have to read all his books again.

MichaelHW

Active member

As much as I like Ken Follett, he is no Graham Greene. Greene could write anything: serious, funny, political, suspense, everything was brilliant. His foreign policy analyses were always spot on (The Comedians, The Quiet American etc). Ken Follett is a brilliant story teller who can create a very fascinating suspense story. The setting is perfect, the language flawless. The composition is good. But there is no analytical subtext. I have not seen many interesting analytical sides to what he writes, at least. Not even in his biotech novel The Third Twin. There is not much humor either. It must be said that I have not read his 20th century epic. The reason for that is my own disappointment over the fact that he abandoned stories like The Needle etc. I did read his Middle Ages-saga. I really enjoyed it, but it dragged on too long. But it might be that there are some new things in those latest epic books? I have not read them, and therefore I don't know. Clearly Follett is very good at mixing suspense and historical fact. These are skills I can't remember in Graham Greene. At least they were not a huge part of what Greene did. It is very unusual that writers have such a good command over so many genres, like Greene. So Follett is no worse off in this respect than most other writers. (Ibsen wrote the most boring comedies I know. His other plays are what made him famous.)I believe it! That novel you’ve described sounds cool…is KF anything like Graham Greene? I guess you have me picturing this avuncular-type figure whose stuff seems to ‘entertain’ initially before coalescing into some really profound thing. Meanwhile, here I am still working on good ol’ PH, lol.

I can see how this guy gets pegged as a ‘living classic.’ His stuff messes with my head (in a good way). The effect is psychedelic for me. I get why he wrote a whole novel about some guy who really, um, liked mushrooms.

Has anyone else here either pre-ordered “The Fruit Thief” or read it in another language? I think someone here said it was a factor in the SA awarding him. I can’t wait to read it, but have to wait for the English edition. ?

The reason why I bring it up is because I’m wondering if anyone else noticed how PH mentions the ‘fruit thief’ concept in a couple of other books. He refers to it in “Crossing the Sierra de Gredos” as a centrally defining image in the banker’s life. He mentions it somewhere else too…I want to say “Moravian Nights,” but I’m not positive, will have to read all his books again.

Last edited:

bacon

Active member

Here's a just-published New Yorker piece on the controversy surrounding Peter Handke's Nobel Prize in Literature award. Subscribers only, unfortunately. But give the link a try, you may be able to read it as one of the initial free articles they offer to non-subscribers.

www.newyorker.com

www.newyorker.com

On December 10, 2019, the Austrian writer Peter Handke received the Nobel Prize in Literature. If he felt pride or triumph, he didn’t show it. His bow tie askance above an ill-fitting white dress shirt, his eyes unsmiling behind his trademark round glasses, Handke looked resigned and stoical, as if he were submitting to a bothersome medical procedure. As he accepted his award, some of the onlookers—not all of whom joined in the applause—appeared equally grim.

Handke embarked on his career, in the nineteen-sixties, as a provocateur, with absurdist theatrical works that eschewed action, character, and dialogue for, in the words of one critic, “anonymous, threatening rants.” One of his early plays, titled “Offending the Audience,” ends with the actors hurling insults at the spectators. In the following decades, as he produced dozens of plays and novels, he turned his experiments with language inward, exploring both its possibilities and its limitations in evoking human consciousness. W. G. Sebald, who was deeply influenced by Handke, wrote, “The specific narrative genre he developed succeeded by dint of its completely original linguistic and imaginative precision.”

...

Literature’s Most Controversial Nobel Laureate

Peter Handke’s defenders argue that his views on Serbia are extraneous to his literary achievement, but a close reading of his output suggests otherwise.

On December 10, 2019, the Austrian writer Peter Handke received the Nobel Prize in Literature. If he felt pride or triumph, he didn’t show it. His bow tie askance above an ill-fitting white dress shirt, his eyes unsmiling behind his trademark round glasses, Handke looked resigned and stoical, as if he were submitting to a bothersome medical procedure. As he accepted his award, some of the onlookers—not all of whom joined in the applause—appeared equally grim.

Handke embarked on his career, in the nineteen-sixties, as a provocateur, with absurdist theatrical works that eschewed action, character, and dialogue for, in the words of one critic, “anonymous, threatening rants.” One of his early plays, titled “Offending the Audience,” ends with the actors hurling insults at the spectators. In the following decades, as he produced dozens of plays and novels, he turned his experiments with language inward, exploring both its possibilities and its limitations in evoking human consciousness. W. G. Sebald, who was deeply influenced by Handke, wrote, “The specific narrative genre he developed succeeded by dint of its completely original linguistic and imaginative precision.”

...

Liam

Administrator

^A very interesting piece, but a little bit inconclusive (perhaps in keeping with Handke's own narratives?) The author doesn't reach anything resembling a definitive conclusion about the value of Handke's work; she also doesn't say if she approves or disapproves of his Nobel: where does she stand, as a conscientious reader, on this issue? But I read it with pleasure: a well-written, broadly argued perspective!

Bartleby

Moderator

It was an interesting read, yes. Where I think she fails is (his political writings aside, which I understand why one should expect them to be less dialectical, to borrow her wording) in demanding Handke to be a kind of writer he is not, and he is great in what he does. It’s something that keeps baffling (if not simply bothering) me, this failure, or maybe insistence, to read something and see the value in it for what it’s trying to achieve, instead of wanting it to reflect your ideal of what literature should be. She seems to find a fault in the writer’s approach of seeing things subjectively (while acknowledging other subjectivities), of his surface-level view of the world, comparing him, unfavorably, to the American post-modernists, who wrote out of political distaste with the government etc — the thing is, there should always be diverse views in literature, and they should be all equally embraced, for they mean enriching our perspective of others, and they should be valued for their aesthetic contributions to the art form, personal preference taking a step aside in this matter (you can see her bias when she has a beef with a completely non Serbia related passage she quotes from The Fruit Thief, about asking the readers to imagine the music it’s playing in a given scene — she’s completely caught in her antipathy towards Handke’s mishandling of political issues that she, like an obsessive detective, starts seeing connections where there aren’t; or, again, in lieu of appreciating the freedom of his fiction, she is tainted by Handke’s few political works and let them contamine the pure substance of his overall oeuvre). The quotes from Sebald get it right in seeing Handke’s literature as both a representation of anxiety, and, through the almost therapeutic process of the writing, its pacing, its soothing (in the case of Repetition and the works that came after it) invitation to stop all the hustle and walk and look around and really listen to the constant present in front of you with all its unexpected small wonders, a remedy for the melancholy. “You have time”, the narrator of Repetition says to himself near the end of the novel, and just like a narrative, coming into being word after word after word, it reminds us of how we should build our lives, with a focus on the now, step by step.

Leseratte

Well-known member

Thanks for this interesting analytical article, @bacon. I have read very little by Handke up to now, started to read "A sorrow beyond dreams", and was impressed by its intensity, maybe too impressed to finish it.Here's a just-published New Yorker piece on the controversy surrounding Peter Handke's Nobel Prize in Literature award. Subscribers only, unfortunately. But give the link a try, you may be able to read it as one of the initial free articles they offer to non-subscribers.

Literature’s Most Controversial Nobel Laureate

Peter Handke’s defenders argue that his views on Serbia are extraneous to his literary achievement, but a close reading of his output suggests otherwise.www.newyorker.com

On December 10, 2019, the Austrian writer Peter Handke received the Nobel Prize in Literature. If he felt pride or triumph, he didn’t show it. His bow tie askance above an ill-fitting white dress shirt, his eyes unsmiling behind his trademark round glasses, Handke looked resigned and stoical, as if he were submitting to a bothersome medical procedure. As he accepted his award, some of the onlookers—not all of whom joined in the applause—appeared equally grim.

Handke embarked on his career, in the nineteen-sixties, as a provocateur, with absurdist theatrical works that eschewed action, character, and dialogue for, in the words of one critic, “anonymous, threatening rants.” One of his early plays, titled “Offending the Audience,” ends with the actors hurling insults at the spectators. In the following decades, as he produced dozens of plays and novels, he turned his experiments with language inward, exploring both its possibilities and its limitations in evoking human consciousness. W. G. Sebald, who was deeply influenced by Handke, wrote, “The specific narrative genre he developed succeeded by dint of its completely original linguistic and imaginative precision.”

...

From the little I have written by him and about him, Handke seems to be an very interesting and innovative author. He also seems to be someone who likes to go against the grain, taking upon himself to act the bastard, putting himself and his supporters in an uncomfortable position. These is of course very mildly expressed when it comes to the Serbian massacre. It poises the again uncomfortable question, how far the conferring of an award should be influenced by the authors political position.

bacon

Active member

I think her non-stance is informative in its own way. Most writers these days would immediately condemn Handke for past political views without question. Handke's support for Serbs at that time means we should condemn his entire body of work, etc. Which is chilling to me. So maybe a non-condemnation is a sign of, if not support, then at least an acknowledgement that a writer's work and his/her political views / actions are not necessarily always fully entwined and can be viewed as separate things. As to the prying into authors' personal lives, this makes hermit writers seem all the more sagacious. This article made me think of Roman Polanski, Bill Cosby, Woody Allen and a slew of other artists whose personal decisions affected public sentiment towards their artistic work. A touchy subject that makes me question my stance on it all. As to Bartleby's note about subjectivity, I think Handke creates works that make the reader a more active participant, causes them angst and frustration, which is engagement after all. And awarding Handke makes the Nobel Prize committee seem like provocateurs themselves, maybe this is all done to foment conversations about literature and its place in the world.^A very interesting piece, but a little bit inconclusive (perhaps in keeping with Handke's own narratives?) The author doesn't reach anything resembling a definitive conclusion about the value of Handke's work; she also doesn't say if she approves or disapproves of his Nobel: where does she stand, as a conscientious reader, on this issue? But I read it with pleasure: a well-written, broadly argued perspective!

Leseratte

Well-known member

I think you touched a very important point there. Today it´s not enough that our idols excel in writing, in art, in sports, in whatever, they must have at least acceptable public images. Information has become everything. In the past one had less information, there was more privacy. I think SA was aware of it, but chose to disregard it in Handke´s case.So maybe a non-condemnation is a sign of, if not support, then at least an acknowledgement that a writer's work and his/her political views / actions are not necessarily always fully entwined and can be viewed as separate things. As to the prying into authors' personal lives, this makes hermit writers seem all the more sagacious. This article made me think of Roman Polanski, Bill Cosby, Woody Allen and a slew of other artists whose personal decisions affected public sentiment towards their artistic work. A touchy subject that makes me question my stance on it all.

Ben Jackson

Well-known member

Thanks for the clarification about the article, brother. Read the article earlier this morning and I agree with everything you said.It was an interesting read, yes. Where I think she fails is (his political writings aside, which I understand why one should expect them to be less dialectical, to borrow her wording) in demanding Handke to be a kind of writer he is not, and he is great in what he does. It’s something that keeps baffling (if not simply bothering) me, this failure, or maybe insistence, to read something and see the value in it for what it’s trying to achieve, instead of wanting it to reflect your ideal of what literature should be. She seems to find a fault in the writer’s approach of seeing things subjectively (while acknowledging other subjectivities), of his surface-level view of the world, comparing him, unfavorably, to the American post-modernists, who wrote out of political distaste with the government etc — the thing is, there should always be diverse views in literature, and they should be all equally embraced, for they mean enriching our perspective of others, and they should be valued for their aesthetic contributions to the art form, personal preference taking a step aside in this matter (you can see her bias when she has a beef with a completely non Serbia related passage she quotes from The Fruit Thief, about asking the readers to imagine the music it’s playing in a given scene — she’s completely caught in her antipathy towards Handke’s mishandling of political issues that she, like an obsessive detective, starts seeing connections where there aren’t; or, again, in lieu of appreciating the freedom of his fiction, she is tainted by Handke’s few political works and let them contamine the pure substance of his overall oeuvre). The quotes from Sebald get it right in seeing Handke’s literature as both a representation of anxiety, and, through the almost therapeutic process of the writing, its pacing, its soothing (in the case of Repetition and the works that came after it) invitation to stop all the hustle and walk and look around and really listen to the constant present in front of you with all its unexpected small wonders, a remedy for the melancholy. “You have time”, the narrator of Repetition says to himself near the end of the novel, and just like a narrative, coming into being word after word after word, it reminds us of how we should build our lives, with a focus on the now, step by step.

Bartleby

Moderator

I’ve got it on my kindle already, but I have so many novels and texts to read for uni that it’s hard to focus on anything else right nowThe Fruit Thief came out in hardcover a few days ago but I don't have any free time at the moment to read it, ?

Besides, I’d really like to read Crossing the Sierra de Gredos first. Although this order of reading is not necessary, The Fruit Thief is somewhat connected with that novel (the woman in Crossing... looking for her daughter apparently being the mother of the fruit thief from the eponymous book... who in turn is looking for her mother). I believe I’ve read there’s some sense of closure at the of Thief. Thing is, Crossing... is sooo much longer ?

MichaelHW

Active member

I’ve got it on my kindle already, but I have so many novels and texts to read for uni that it’s hard to focus on anything else right now

Besides, I’d really like to read Crossing the Sierra de Gredos first. Although this order of reading is not necessary, The Fruit Thief is somewhat connected with that novel (the woman in Crossing... looking for her daughter apparently being the mother of the fruit thief from the eponymous book... who in turn is looking for her mother). I believe I’ve read there’s some sense of closure at the of Thief. Thing is, Crossing... is sooo much longer ?

I have always had the impression that Handke was a little stiff and intellectual in his writing? It has been a while since I even opened one of his books. But this impression stuck with me, somehow. Am I right?

nagisa

Spiky member

This Friday I had the occasion to see a recent play called "The Handke Project: Or, Justice for Peter’s Stupidities". I had stumbled on it a couple of years back combing over the theatrical offer here in Florence; it seems it is some how connected to Teatro della Pergola, though I saw it it in Teatro Rifredi. Anyway, the title and premise were certainly enticing...

ABOUT THE SHOW

For an artist, where does the freedom of speech end, and the need to be politically conscious begin? Can we create art without being insensitive? Can we separate the art from the artist? These are among the important questions asked in a new production from Kosovan theatre company Qendra Multimedia. The Handke Project follows Qendra’s recent successful tour of Balkan Bordello, which played across South Eastern Europe and at New York’s legendary La MaMa theatre.

The Handke Project takes as its central theme the controversial decision to convey the honour of Nobel Laureate for Literature on Austrian writer Peter Handke, in spite of his well-documented support for Slobodan Milosevic – who died while on trial for war crimes at The Hague – a support which extended to speaking at Milosevic’s graveside. In The Handke Project, Qendra takes this controversy as a jumping off point to explore how art is appreciated and promoted when it crosses the boundaries of basic decency, humanism or ethics.

To create the production, Qendra have assembled a pan-European ensemble of writers, performers and creatives from Kosovo, Italy, Germany, Croatia, Serbia and others, each bringing their own unique perspective to the work. They include the celebrated Serbian playwright Biljana Srbljanovic who will act as dramaturg, and Germany-based Croatian writer Alida Bremer who has written extensively on Handke for the German press.

Handke Project is a theatrical performance about the writer who with his books and opinions has fabricated and overturned facts of the wars in former Yugoslavia; has incited and supported ‘the scorched earth’ ideology; as well as managed to sing praises to militant poets and filmmakers converted into ‘engineers of genocidal projects.’ During the funeral of the war criminal Milosevic, Handke said to the blood-thirsty mass of people that he “does not know the truth” and that is why he is, “there close to Milosevic, close to Serbia.” Handke compared the suffering of Serbs to the suffering of Jewish people during Nazism!

Artists and scholars from Kosovo, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Italy, North Macedonia, France, Montenegro, and Germany will discuss and address “Peter’s stupidities,” in light of the war in Ukraine and in a time when many cultural institutions in Europe demand from Russian artists to publicly declare their political stance towards the war in Ukraine. A red line is being drawn over all those Russian artists who in one way or another support Putin and the war.

Meanwhile, Handke and the European handkists continue to roam freely, even on top of the eight thousand graves of the Srebrenica victims. Thus, as Eric Gordy beautifully put it: Handke is kitsch! But a Nobel Prize for him is also kitsch. Handke’s supporters, too, are kitsch. Finally, the European hypocrisy is itself kitsch.

A pan-European troupe of artists, from Kosovo, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Italy, North Macedonia, France, Montenegro, and Germany, taking on Handke and calling him out theatrically. I had high hopes!

It has some reviews and explainers. At its core, it is a non-linear exploration of what a troupe of such artists could present as a play satirising Handke (and not get sued by Suhrkamp!).

A beginning with a solemn injunction to leave the room immeadiately if one is a fascist, racist, homophobe, etc, fake-interrupted by a woman in the audience who agrees with the sentiment but won't take injunction and expects a serious dive into Handke (and joins the troupe of course; not their best trick).

Increasingly manic saynettes, with some actual deep Handke cuts; memorable ones are:

Saynettes bleeding out of the fourth wall; the Serb member storms off so the remaining members improvise a casting call, recalling that the actor/ess must be prepared "to not be able to work in Serbia again for at least five years" and that "insurance unfortunately cannot be provided for the inevitable bomb that wil hurtle through their family's window". Followed by ironically erotic dancing to shrill titles in the Serb rag press lamenting the attacks on Handke "Handke, Friend of the Serbian People, Unfairly Slandered and Maligned!" "Handke, Our Saintly Defender, Unjustly Attacked!". Etc.

Less well done were the (unfortunately key) scenes of a little boy skiing in the mountains. A Bosnian boy called by his father in the forest as the Serbian militias close in — innocence over the 8000 graves of Srebrenica. The image recurs three times but is too vague and slow at first to evoke much, and a bit ham-handedly explained finally.

Ham-handed, a bit unfortunately, is what I retain for quite a few parts. It's fun, but feels a bit... college-avant-guard-y? Breaking the wheel and thinking you're doing it in a cleverer fashion than those who broke the wheel before you. There is a genuine, at times deep and effective engagement with Handke's texts. Though less his actual theatre I believe; of course they reference Insulting the Public (how could they not!), but eg the satire of Handke's Dugout play and prelapsarian vision of intra-Balkan relations was which too brief and superficial for such a rich material.

All in all though, it is all the more enjoyable the more one has read Handke — critically, I suppose. Not like the fainting aesthete of the quite funny scene who will literally die if she cannot find her Handke book, you understand, all that war stuff is so complicated, those people over there killing each other (and are they really killing each like they say they are?) in that beautiful unspoiled land, spoiled now because of the world, because of base thigs erupting in the green of the tree and the brown of the mountain and the bark, you don't understand please I need Handke's book, his beauty is what allows me to live (—meanwhile bodies on the ground with plastic bags over their heads sporadically writhe and gasp for breath).

Very niche, and execution left something to be desired, a bit half-baked/recooked postmodern theatre. Still, if one is in the niche, very fun.

ABOUT THE SHOW

For an artist, where does the freedom of speech end, and the need to be politically conscious begin? Can we create art without being insensitive? Can we separate the art from the artist? These are among the important questions asked in a new production from Kosovan theatre company Qendra Multimedia. The Handke Project follows Qendra’s recent successful tour of Balkan Bordello, which played across South Eastern Europe and at New York’s legendary La MaMa theatre.

The Handke Project takes as its central theme the controversial decision to convey the honour of Nobel Laureate for Literature on Austrian writer Peter Handke, in spite of his well-documented support for Slobodan Milosevic – who died while on trial for war crimes at The Hague – a support which extended to speaking at Milosevic’s graveside. In The Handke Project, Qendra takes this controversy as a jumping off point to explore how art is appreciated and promoted when it crosses the boundaries of basic decency, humanism or ethics.

To create the production, Qendra have assembled a pan-European ensemble of writers, performers and creatives from Kosovo, Italy, Germany, Croatia, Serbia and others, each bringing their own unique perspective to the work. They include the celebrated Serbian playwright Biljana Srbljanovic who will act as dramaturg, and Germany-based Croatian writer Alida Bremer who has written extensively on Handke for the German press.

Handke Project is a theatrical performance about the writer who with his books and opinions has fabricated and overturned facts of the wars in former Yugoslavia; has incited and supported ‘the scorched earth’ ideology; as well as managed to sing praises to militant poets and filmmakers converted into ‘engineers of genocidal projects.’ During the funeral of the war criminal Milosevic, Handke said to the blood-thirsty mass of people that he “does not know the truth” and that is why he is, “there close to Milosevic, close to Serbia.” Handke compared the suffering of Serbs to the suffering of Jewish people during Nazism!

Artists and scholars from Kosovo, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Italy, North Macedonia, France, Montenegro, and Germany will discuss and address “Peter’s stupidities,” in light of the war in Ukraine and in a time when many cultural institutions in Europe demand from Russian artists to publicly declare their political stance towards the war in Ukraine. A red line is being drawn over all those Russian artists who in one way or another support Putin and the war.

Meanwhile, Handke and the European handkists continue to roam freely, even on top of the eight thousand graves of the Srebrenica victims. Thus, as Eric Gordy beautifully put it: Handke is kitsch! But a Nobel Prize for him is also kitsch. Handke’s supporters, too, are kitsch. Finally, the European hypocrisy is itself kitsch.

A pan-European troupe of artists, from Kosovo, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Italy, North Macedonia, France, Montenegro, and Germany, taking on Handke and calling him out theatrically. I had high hopes!

It has some reviews and explainers. At its core, it is a non-linear exploration of what a troupe of such artists could present as a play satirising Handke (and not get sued by Suhrkamp!).

A beginning with a solemn injunction to leave the room immeadiately if one is a fascist, racist, homophobe, etc, fake-interrupted by a woman in the audience who agrees with the sentiment but won't take injunction and expects a serious dive into Handke (and joins the troupe of course; not their best trick).

Increasingly manic saynettes, with some actual deep Handke cuts; memorable ones are:

- Childhood Story - him as child taking instruction on how to be the best writer from uncle fascism in a black hoop skirt ("Use your beautiful question marks!"). Recalled also later in a surreal sequence with a devil and angel (chiming with The Sky over Berlin/Wings of Desire as well)

- Essay on the Mushroom-Mad Man - him waiting in a garden grilling (poisonous) mushrooms pointedly not waiting for the call from the SA (I can't find it with a cursory search, but I think he had some salty things to say about the prize before he got it)

- The Cuckoos of Velika Hoca - the sequence on Handke donating prize money to a specific tiny serb village in Kosovo to build, of all things, a pool. Next to an annihilated kosovar village. Which never gets built in the end because no one agrees where to put it. Based on a true story.

- A Sorrow Beyond Dreams - maybe not exactly a deep cut, since it is one of his best-known works (and rightfully so); but a deep cut in the sense that they mock his mother's suicide — as he mocked the mothers of Srebrenica... I did gasp when they went there.

Saynettes bleeding out of the fourth wall; the Serb member storms off so the remaining members improvise a casting call, recalling that the actor/ess must be prepared "to not be able to work in Serbia again for at least five years" and that "insurance unfortunately cannot be provided for the inevitable bomb that wil hurtle through their family's window". Followed by ironically erotic dancing to shrill titles in the Serb rag press lamenting the attacks on Handke "Handke, Friend of the Serbian People, Unfairly Slandered and Maligned!" "Handke, Our Saintly Defender, Unjustly Attacked!". Etc.

Less well done were the (unfortunately key) scenes of a little boy skiing in the mountains. A Bosnian boy called by his father in the forest as the Serbian militias close in — innocence over the 8000 graves of Srebrenica. The image recurs three times but is too vague and slow at first to evoke much, and a bit ham-handedly explained finally.

Ham-handed, a bit unfortunately, is what I retain for quite a few parts. It's fun, but feels a bit... college-avant-guard-y? Breaking the wheel and thinking you're doing it in a cleverer fashion than those who broke the wheel before you. There is a genuine, at times deep and effective engagement with Handke's texts. Though less his actual theatre I believe; of course they reference Insulting the Public (how could they not!), but eg the satire of Handke's Dugout play and prelapsarian vision of intra-Balkan relations was which too brief and superficial for such a rich material.

All in all though, it is all the more enjoyable the more one has read Handke — critically, I suppose. Not like the fainting aesthete of the quite funny scene who will literally die if she cannot find her Handke book, you understand, all that war stuff is so complicated, those people over there killing each other (and are they really killing each like they say they are?) in that beautiful unspoiled land, spoiled now because of the world, because of base thigs erupting in the green of the tree and the brown of the mountain and the bark, you don't understand please I need Handke's book, his beauty is what allows me to live (—meanwhile bodies on the ground with plastic bags over their heads sporadically writhe and gasp for breath).

Very niche, and execution left something to be desired, a bit half-baked/recooked postmodern theatre. Still, if one is in the niche, very fun.